Overview

The purpose of this guidance is to help iHARP project members make decisions regarding digital object management for their projects. It will also serve as the basis for data management training sessions provided by TACC staff for iHARP projects. A digital object is any born-digital piece of information and its related metadata. Examples of digital objects include raw or processed data in discrete digital files, documentation, and software or code (including models). Digital objects include informational content as well as metadata that supports administration, access, and preservation.

Background

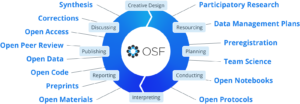

Open Science (also sometimes called Open Knowledge) is “the principle and practice of making research products and processes available to all, while respecting diverse cultures, maintaining security and privacy, and fostering collaborations, reproducibility, and equity.”[1] Open Science itself is not a new concept—it’s an umbrella term that encompasses many open initiatives that have been building steam for many years.

Image from: https://www.cos.io/open-science

The ultimate goals of Open Science are to improve the availability of research products and enable greater reproducibility of results. Open Science emphasizes openness at every stage of scientific inquiry—using open source code, open data, reading and publishing Open Access articles, and contributing open products back to the research ecosystem. Open Science should be practiced by all members of research teams at every level—from senior PIs to undergrads.

One way to conceptualize Open Science is to think of it in terms of the USE – MAKE – SHARE framework: USE – discover existing resources and use them in your project; MAKE – create a management plan for new resources you’ll generate through your work; SHARE – publish your research products in open repositories, with applicable licenses, robust metadata and documentation, and make sure you have a permanent identifier (PID).

What should members of iHARP be doing right now?

- Education

- Read about Open Science at the Center for Open Science or Opensciency.

- Understand the FAIR and CARE principles and how that relates to research impacts on Indigenous communities.

- Data and Code Reuse

- Use FAIR, open data and open source software where possible.

- Use data that has been published in a domain science or institutional repository such as Pangaea or Zenodo. You can use an aggregator such as Re3data or FAIRSharing to search for repositories.

- Understand the provenance and quality of the digital objects you reuse : Where did it come from? How has it been cleaned or manipulated? Does the dataset have a DOI, quality metadata, a data report, is the data quality controlled, etc.?

- Researchers often default to using datasets they are already aware of or encouraged to use by collaborators.

- Without learning data literacy skills such as how to locate datasets or how to evaluate them, researchers are still at risk of putting bad data into their models.

- Data and Code Sharing

- Each project team should identify a data manager to understand and document data resources utilized by the team.

- As you collect data and curate datasets, make sure you are incorporating FAIR guidance at every level of your work.

- Document and share your code via tools like GitHub.

- Open Science emphasizes provenance so robust metadata and documentation are key. If you focus on creating documentation and metadata as you work, it will save the heavy lift of preparing everything at the end of your project.

- Publication

- Prioritize publishing in Open Access journals if possible.

- Publish datasets in repositories such as Pangaea or Zenodo.

- Publish your code using a method such as this connection between GitHub and Zenodo.

Guiding Principles

TACC encourages users to follow best practices generally accepted for free and open source software (FOSS), data management (FAIR Principles), and other relevant disciplinary standards. We encourage our partners to familiarize themselves with these:

- FAIR (findable, accessible, interoperable, reusable) Principles https://www.go-fair.org/fair-principles/

- Principles for Digital Development: https://digitalprinciples.org/principle/use-open-standards-open-data-open-source-and-open-innovation/

- What is FOSS? https://itsfoss.com/what-is-foss/

Writing a Data Management or Open Science Plan

A data management plan (DMP) is a document that outlines how you will manage your research data throughout the entire research project. It can also be thought of as a standard operating procedure (SOP) document. DMPs usually include details on how you will collect, store, and share your data, as well as how you will ensure its long-term preservation. The goal of a data management plan is to help you organize your data in a way that is efficient, secure, and sustainable, while also meeting the requirements of funding agencies, publishers, and other stakeholders. A data management plan is an important tool for ensuring that your research data is properly managed and can be shared and reused by others in the future.

Increasingly, funding agencies are moving towards a new model for DMPs that requires treating software, models, code, etc., in the same way as data—in other words, newer DMPs require outlining plans for the creation, storage, and publishing of all research products produced as part of a funded project. These new plans are sometimes called a “data management and sharing plan” (DMSP) or an open science plan (OSP). OSP or DMSP also specifically requires information on plans to share or publish research products, not just how those digital objects will be stored and preserved. They also direct researchers to prioritize the reuse of existing data or models.

You can use a DMP or DMSP to document your decisions regarding digital objects, either as a required part of a grant application or for use by your individual project team. Each iHARP project team should consider crafting a DMP or DMSP that covers the work carried out on that project.

- DMPTool, a resource for creating DMPs using templates based on guidelines for specific disciplines or funding agencies: https://dmptool.org/

- NSF guidance on Data Management and Sharing Plan preparation: https://new.nsf.gov/funding/data-management-plan

Identifying a Data Manager

TACC encourages research or project groups to identify a designated data manager. The person in this role will act as the responsible party for following and enforcing the data management plan for the research group or project. The data manager can assist with folder organization guidelines, file naming conventions, and other data management tasks, and provides guidance to other members of the team. Identifying a designated data manager allows TACC to provide recommendations and support more efficiently. From TACC’s perspective, it helps us to have a single point of contact for managing permissions (for example, through Access Control Lists [link: https://docs.tacc.utexas.edu/tutorials/acls/]) and who can serve as an “owner” of the data in a collection.

In addition, funding agencies such as the NSF are now requiring the identification of key project personnel responsible for digital object management tasks in the data management sharing plans they require as part of new grant applications.

Regularly Review Digital Object Management Activities

It is advisable for project teams to establish a timeline and regular schedule to review digital object management activities so that all members of the team are aware of their responsibilities and keeping on track with the data management plan. This can help from overwhelming individuals who suddenly find that there are a myriad number of tasks that need to be completed in a rushed timeframe, such as needing to curate and package data to publish alongside a peer-reviewed paper or to complete yearly reports to funding agencies. Building digital object management check-ins to regular team meetings helps keep these responsibilities on everyone’s minds.

Creating and Saving Digital Objects

File Formats

When working with digital objects, it is important to consider the file format being used to store your digital objects. Some file formats are proprietary and can only be created or modified using specific software. These formats may become obsolete or unsupported in the future, making it difficult or impossible to access your digital objects. In general, we encourage our partners to prioritize using non-proprietary or open file types (e.g., tabular data in .csv format, text in .txt or .rtf format, .json for structured data). Consider using a file format that is widely used and supported by multiple software tools and platforms. This can help ensure that your digital objects can be easily accessed and used by others.

Further reading:

- MIT Libraries’ guidance on file formats for long-term preservation: https://libraries.mit.edu/data-management/store/formats/

- DataONE best practice guidance: https://dataoneorg.github.io/Education/bestpractices/document-and-store

Descriptive File and Folder Names

TACC encourages our users to develop a method for naming the folders and files they are generating and working with, and to use it consistently for all their files. This will make it easier to find files on your computer and create and share compressed archives with others. While TACC can help your team think through different organizational methods and naming conventions, the development of these guidelines is a “your mileage may vary” situation and should be tailored to your specific project or team. What is your current project? What are the individual pieces or components of your project? Try drawing it out on a piece of paper from the top level down to the smallest components. It may help you think about how to organize your information by thinking about your project in this way.

These resources can help you think through the design of your organizational system:

- MIT Libraries best practices: https://libraries.mit.edu/data-management/store/organize/

- DataONE best practice guidance: https://dataoneorg.github.io/Education/bestpractices/assign-descriptive-file

Preserving and Sharing Digital Objects

Long-term Curation and Preservation

An important part of long-term preservation is planning what digital objects you will keep and how you will store them. How much storage will you need? Is there a need for storing the raw data, or only processed data? How many versions of a model or piece of software do you need to keep?

Here are some basic guidelines for preserving and storing digital objects for the long term:

- Choose the right storage media – The storage media you use should be durable and reliable, such as hard drives or cloud storage. Avoid using media that can degrade over time, such as CDs or DVDs, or media that can be easily misplaced, such as a USB drive.

- It is important to remember that cloud storage is not a perfect solution. Cloud storage provided by industry (such as Amazon AWS, Microsoft Azure, or Google Cloud) can quickly become prohibitively expensive, while institutional cloud storage, such as Box or Microsoft OneDrive, may not be available after a student graduates or leaves a project.

- TACC’s Corral system provides high-reliability, high-performance storage for research requiring persistent access to large quantities of structured or unstructured data. For more information, see: https://iharp.umbc.edu/resources/tacc-computing/#data

- Use non-proprietary file formats – Non-proprietary file formats are more likely to be supported in the future and can be accessed by a wider range of software and tools.

- Keep multiple copies of your digital objects – Store your digital objects in multiple locations, such as on different hard drives or in cloud storage, to reduce the risk of loss due to hardware failure, theft, or natural disasters.

- Corral utilizes a system of “snapshots” to create short-term backups of files on the system. See more information: https://docs.tacc.utexas.edu/hpc/corral/#snapshots

- Keep track of your digital objects – Use consistent naming conventions and metadata to keep track of your digital objects and make it easier to locate specific files. Create data dictionaries and ReadMe files to document changes to data or code.

- Plan for obsolescence – Technology changes quickly, so plan for the eventual obsolescence of your storage media, file formats, and software tools. Migrate your digital objects to new formats and storage media periodically.

- Check your digital objects regularly – Periodically check your digital objects to make sure they are still accessible and usable. This can help you catch any problems early and prevent loss.

- Store your digital objects in a trusted repository – Consider using a trusted repository, such as an institutional repository or a data archive, to ensure that your digital objects are stored securely and in a way that meets professional standards for long-term preservation.

You should also keep in mind any requirements from your funding source or institution regarding data preservation. Check with your funding agency to find out if there is a specific policy that spells out a data retention period. For publicly funded research in the US, this is often a minimum of three years. It is better to aim for even longer, if possible, in case you or someone else needs the data later on. Five to ten years is a good rule of thumb. Some institutions or agencies have data retention policies (such as this one, from Cornell) that define what data is preserved and for how long. If your institution or agency has a retention policy, you can review it for applicability to your project.

Repositories

In addition to long-term preservation, some funding agencies require that research products are made accessible through a publicly accessible repository such as data.gov or a subject-specialized repository. Some publishers also require upload to a repository as part of the acceptance and publication process for peer-reviewed journal articles. An increasing number of universities or university consortia have data repositories for publishing research data produced at their institutions. An example of this is the Texas Data Repository, which is available to researchers whose institutions are members of the Texas Digital Library.

There are also many resources for looking up subject or program-specific repositories:

- re3data.org, the Registry of Research Data Repositories – Re3data is a global registry of research data repositories that covers research data repositories from different academic disciplines.

- NIH’s tool for repositories for sharing scientific data: https://sharing.nih.gov/data-management-and-sharing-policy/sharing-scientific-data/repositories-for-sharing-scientific-data

- Zenodo, a general Open Science repository created at CERN: https://zenodo.org/

Choosing a License

One of the most important considerations regarding sharing your digital objects is how you license them for reuse and adaptation. There are a number of factors to consider when choosing a license: whether or not you want to be credited for the digital objects; whether or not you want to allow adaptations of your digital objects; whether or not you will allow commercial reuse of your digital objects. Many state and federal government agencies use public domain licenses such as Creative Commons CC0.

Data licenses information:

- License Your Data by Mozilla Science: https://mozillascience.github.io/open-data-primers/3.4-licensing.html

- Creative Commons Choose a License tool: https://creativecommons.org/share-your-work/

- Choose A License from GitHub (focused on software licenses): https://choosealicense.com/

It’s important to remember that you can only apply a license to digital objects that you or your project team created. If you are part of a university, your library might provide guidelines specific to your institution that you can follow.

Creating a readme file

When sharing a collection of data, it’s helpful to create a “readme” file that can explain some of the important collection, curation, and accessibility decisions you’ve made regarding your data. This can make it easier for others to locate and use your data, even if they are not familiar with the specific tools or software used to create it. While you can include this information in the metadata associated with your data, a readme file allows you to more fully describe processing steps, software versions used to collect and manage the data (and/or which software are compatible with your data), collection methodology, etc., in a more human-readable format.

- Cornell guide to writing descriptive readme files: https://data.research.cornell.edu/content/readme

Additional Resources

- Cornell’s Research Data Management Services

- Data Management Planning: https://data.research.cornell.edu/content/data-management-planning

- Best Practices: https://data.research.cornell.edu/content/best-practices

- Research Data Management@Harvard

Click here to access a copy of this guidance in a separate browser tab.